This Koren Tanach is an exceptionally beautiful book. If you’re looking to study the Hebrew Bible, I highly recommend it: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

Davidson’s Hebrew/Chaldee Lexicon is the only book I know that can help you translate the entire Hebrew bible: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

The Divine Council of Creation: A Trinitarian Reflection on "Let Us Make Man in Our Image"

In the opening chapter of Genesis, we encounter a profound and mysterious declaration: "Then God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness’" (Genesis 1:26). For centuries, theologians, scholars, and believers have wrestled with the plural language here—"Let us make," "in our image"—spoken by a God who is repeatedly affirmed as one. From a Trinitarian perspective, this verse offers a breathtaking glimpse into the nature of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, a unity of essence expressed in a plurality of persons, working in harmony to create humanity as the crown of creation.

The Plurality of "Elohim" and the Unity of "Bara"

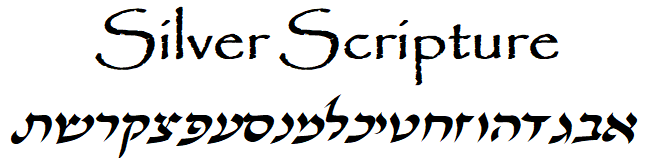

The Hebrew word for God in Genesis 1 is Elohim, a term that carries an intriguing linguistic feature: it appears plural in form, often used in Scripture to denote multiple gods or beings (e.g., Psalm 82:1). Yet, when referring to the one true God of Israel, Elohim is consistently paired with singular verbs. In Genesis 1:1, we read, "In the beginning, Elohim bara—God created." The verb bara (created) is singular, signaling that this Elohim is not a fragmented plurality but a unified singularity. This pattern holds throughout the Hebrew Scriptures: Elohim speaks, acts, and reigns as one, even while bearing a name that hints at multiplicity.

From a Trinitarian lens, this duality-in-unity finds its fullest expression in the New Testament revelation of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The plural form of Elohim suggests a richness within God’s being—a communion of persons—while the singular verb bara underscores their oneness in essence and purpose. When God says, "Let us make man," we hear the divine persons deliberating together, a conversation within the Godhead that reflects their eternal relationship of love and mutual will.

"Let Us": A Divine Act, Not a Delegation

Some have proposed that God’s "Let us" in Genesis 1:26 is an address to the heavenly host, a call to angels to assist in creation. Yet, this interpretation falters under closer scrutiny, especially when compared to a parallel moment in Genesis 11. At the Tower of Babel, God declares, "Come, let us go down and there confuse their language" (Genesis 11:7). Here, too, we see the plural "let us," but the context makes it clear that this is God Himself acting, not delegating to angels. The result—confounded languages—is an act of divine judgment and power, not an angelic intervention.

If "let us go down" at Babel refers to God alone, then "let us make man" in Genesis 1:26 likely follows the same pattern. Scripture reserves the act of creation—particularly the creation of humanity—for God alone. Isaiah 44:24 declares, "I am the Lord, who made all things, who alone stretched out the heavens, who spread out the earth by myself." Angels, as created beings, lack the power to create ex nihilo or to impart the divine image. Thus, the "us" of Genesis 1:26 cannot be a summons to the angelic court but rather an inner dialogue within God Himself—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in perfect unity, determining to fashion humanity as a reflection of their communal nature.

While Scripture does not explicitly state whether angels were present to hear the divine utterance of 'Let us make man in our image,' their absence from the creative act itself remains clear. We cannot know with certainty if the heavenly host stood as silent witnesses to this sacred moment, privy to the counsel of the Godhead, or if the words were spoken solely within the eternal communion of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. What we do know is that the power to create—and to imprint the divine image—belongs to God alone, rendering angelic participation unnecessary, whether they heard the declaration or not.

The Image of God: A Trinitarian Imprint

The very next verse, Genesis 1:27, deepens this mystery: "So God [Elohim] created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him." Here, the plural "our image" of verse 26 transitions to the singular "His image" in verse 27. This seamless shift reinforces the Trinitarian insight: the "us" and the "His" are one and the same. Humanity is created in the image of a God who is both singular and plural—a unity of essence shared by three distinct persons.

This image includes relationality, for the Trinity is an eternal community of love. Humans, made male and female (Genesis 1:27), reflect this relational essence, called to love, create, and rule in harmony, just as the triune God does. It also includes authority, as humanity is given dominion over creation (Genesis 1:28), mirroring the sovereign reign of Father, Son, and Spirit.

The New Testament Revelation: Trinity Unveiled

While Genesis 1:26 offers a veiled hint of God’s triune nature, the New Testament brings this mystery into sharper focus. Jesus, the Son, declares, "I and the Father are one" (John 10:30), and promises the Spirit as "another Helper" (John 14:16), distinct yet united with the Father and Himself. The Great Commission in Matthew 28:19 commands baptism "in the name [singular] of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit [three persons]," encapsulating the one God in three.

Thus, when we revisit Genesis 1:26 through this lens, the words "Let us make man in our image" resonate as a Trinitarian anthem. The Father, the Son, nd the Holy Spirit—all three sharing one divine will, one divine image, one divine glory. Far from a mere grammatical quirk, the plural "us" and the name Elohim point to a God who is both one and many, a unity in diversity revealed fully in Christ and the Spirit.

Conclusion: Bearing the Image of the Triune God

The declaration "Let us make man in our image" is no casual utterance—it is a window into the heart of God’s being. From a Trinitarian perspective, it reveals a God who is not solitary but relational, not static but dynamic, not distant but intimately involved in shaping humanity to reflect His nature. The interplay of Elohim’s plurality with the singularity of bara, the exclusion of angels from the creative act, and the shift from "our image" to "His image" all converge to suggest a God who is one in essence yet three in persons. As we bear this divine image, we are invited into the very life of the Trinity—called to love as the Father loves, to serve as the Son serves, and to live by the Spirit’s power. In this, the mystery of na’aseh adam b’tzalmenu finds its ultimate fulfillment.