This Koren Tanach is an exceptionally beautiful book. If you’re looking to study the Hebrew Bible, I highly recommend it: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

Davidson’s Hebrew/Chaldee Lexicon is the only book I know that can help you translate the entire Hebrew bible: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

Exploring "Tohu vaVohu" in Genesis 1:2: What Does it Really Mean?

Genesis 1:2 says, "And the earth was tohu vavohu," a mysterious Hebrew phrase often translated as "formless and void" or "chaos and emptiness." This comes right after Genesis 1:1, where God creates the heavens and the earth, and before He begins shaping the world with light, land, and life. But what exactly does tohu vavohu mean? Scholars and theologians have wrestled with this phrase for centuries, offering different interpretations that range from literal chaos to philosophical ideas. Let’s break down some of the main views in a way that’s easy to grasp, even if you’re new to the Bible or Hebrew.

The Basic Translation: "Formless and Void"

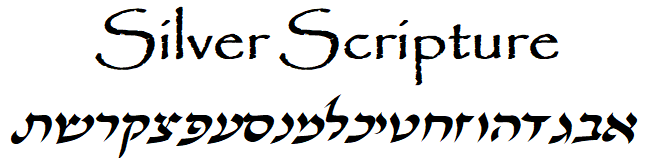

The most common translation of tohu vavohu is "formless and void." Tohu means something like "waste" or "emptiness," and vohu (sometimes spelled bohu) suggests "desolation" or "nothingness." Together, they paint a picture of the earth as a blank slate—no shape, no structure, just a barren, empty mess. This fits the story: God starts with nothing recognizable and then brings order step by step, like an artist working on a blank canvas. Many modern Bibles, like the NIV or ESV, stick with this idea, keeping it simple: the earth was undeveloped and waiting for God to give it purpose.

Chaos and Disorder

Some ancient Jewish and Christian thinkers saw tohu vavohu as more than just emptiness—they thought it meant chaos or disorder. In this view, the earth wasn’t just empty; it was wild and unruly, like a stormy sea or a jumbled mess. The Jewish philosopher Philo and some rabbis linked it to Greek ideas of a chaotic "prime matter" that God tamed. This interpretation ties into Genesis 1:2’s mention of "darkness" and "the deep" (a watery abyss), suggesting a turbulent state that God conquers by creating light and separating things like land and sky. It’s less about nothing and more about something messy that needs fixing.

A Pre-Creation State

Another take, hinted at by Rashi and others, is that tohu vavohu describes a state before God’s main creative work in Genesis 1:1. Rashi, for example, thought water and other elements might have existed already, and tohu vavohu could reflect that unformed, pre-organized stuff. This view sees verse 2 as a flashback: God made the raw materials (heavens and earth), but they were still a shapeless blob until He started shaping them. It’s like saying the earth was in a "rough draft" phase—there, but not yet finished or functional.

"Nothingness" and Creation Out of Nothing

Nachmanides (Ramban), on the other hand, tied tohu vavohu to his belief that God created everything out of nothing. He saw tohu as "formlessness" and vohu as "emptiness," but went deeper, suggesting they represent an absolute lack of anything—no matter, no order—until God spoke. For him, Genesis 1:2 isn’t about chaos or pre-existing stuff; it’s a poetic way to say the earth didn’t even exist in any real way until God gave it form. This fits his view of Genesis 1:1 as the total beginning, with tohu vavohu showing how helpless and nonexistent the world was without God’s action.

A Symbolic or Mystical Meaning

Some later Jewish mystics, like those in the Kabbalah tradition, gave tohu vavohu a spiritual twist. They saw tohu as a state of potential—everything that could be, but isn’t yet—and vohu as the void where it all takes shape. It’s less about the physical earth and more about cosmic or divine processes, like God’s power unfolding from mystery into reality. This is a bit more abstract, but it shows how the phrase can inspire big ideas beyond just rocks and water.

Targum Onkelos and Targum Yonathan

Onkelos and Targum Yonathan, two ancient Aramaic translators of the Hebrew Bible, provide distinct perspectives on *tohu vavohu* in Genesis 1:2, shedding light on its meaning for their audiences. Onkelos, favoring a direct approach, translates tohu vavohu as "desolateand empty" (tuhu uvahu), portraying the earth as a simple, unformed void—lifeless and ready for God’s creative touch. Targum Yonathan, known for adding interpretive flair, renders it as "desolate and empty" and then expands the idea to suggest the earth was not only chaotic and barren but specifically empty of all humans and animals, highlighting a total absence of life before God’s ordering acts. While Onkelos keeps it minimal, focusing on the earth’s shapeless state, Yonathan’s version paints a more vivid picture of desolation, emphasizing that creatures came later. Together, their translations agree that tohu vavohu describes a starting point of emptiness or disorder, fully dependent on God to bring it to life and purpose.

Other Translations

The ancient translations of the Hebrew Bible into Greek and Latin offer varied insights into the meaning, reflecting different shades of its sense of emptiness or chaos. The Septuagint (LXX), a Greek translation from around the 3rd century BCE, renders tohu vavohu as "invisible and unformed" (*aoratos kai akataskeuastos*), suggesting the earth was shapeless and imperceptible, perhaps emphasizing its lack of order or visibility. The Septuagint’s choice to translate tohu vavohu in Genesis 1:2 as "invisible and unformed" might suggest that its translators saw the earth as "invisible" because God had not yet spoken the words "Let there be light" in Genesis 1:3. This could imply that, without light, the world was hidden or imperceptible, existing in a dark, undefined state until God’s command illuminated and revealed it. The text’s mention of "darkness over the face of the deep" in verse 2 supports this idea, linking invisibility to the absence of light before God’s creative act.

Aquila and Symmachus, later Greek translators, take a more literal approach: Aquila uses "empty and nothing”, sticking close to the Hebrew idea of a void, while Symmachus opts for "fallow and indistinct". (1) The Vulgate, Jerome’s Latin translation from the 4th century CE, translate “inanis et vacua.” Both are terms meaning “empty.” Inanis means lacking substance and vacua means lacking presence. This translation of tohu as inanis aligns with another use of tohu in 1 Samuel 12:21, where it describes turning away form God to "vain" things—idols that are worthless and lack substance. The Vulgate’s *inanis* carries a similar nuance, implying not just emptiness but something without purpose or reality, much like the English word "inane," which can mean silly or insubstantial. Thus, the Vulgate’s choice of inanis echoes this broader sense of tohu as a vain, substanceless state, reinforcing the picture of an earth that’s not only formless but utterly devoid of meaning until God shapes it.

Why It Matters

So, what’s the takeaway? Tohu vavohu could mean an empty wasteland, a chaotic mess, a pre-creation state, pure nothingness, or even a spiritual concept. Each view depends on how you read the Hebrew and what you think Genesis is trying to say about God and the world. The simplest idea— "formless and void"—works well: it shows God as the one who takes nothing special and makes it amazing. But all these interpretations remind us that the Bible’s opening lines are deep and invite us to wonder about how everything began. Whether it’s chaos or emptiness, the real point is that God steps in and brings beauty and order to it all.

Source:

Sailhamer, John H. The Pentateuch as Narrative: A Biblical-Theological Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992.1

This book explores the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) as a unified story, focusing on its theological and narrative structure.