This Koren Tanach is an exceptionally beautiful book. If you’re looking to study the Hebrew Bible, I highly recommend it: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

Davidson’s Hebrew/Chaldee Lexicon is the only book I know that can help you translate the entire Hebrew bible: Click HERE to view on Amazon.

The Enigma of 'Ed in Genesis 2:6: Mist, Springs, or Divine Design?

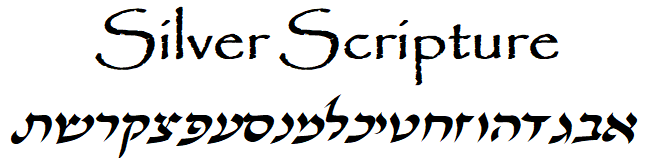

Genesis 2:6 offers a fleeting but fascinating glimpse into the pre-human world: "But there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground" (KJV). The Hebrew term 'ed (אֵד), translated here as "mist," has puzzled translators and commentators alike. Some versions render it "springs" or "streams" (e.g., NIV), others "vapor" or even "cloud." Jewish and Christian traditions have long wrestled with this rare word, drawing on linguistic clues, context, and theology to unpack its meaning. So, what is 'ed, and how do these commentaries guide us?

A Word Shrouded in Rarity

'Ed appears only twice in the Hebrew Bible: Genesis 2:6 and Job 36:27, where it’s often "vapor" or "mist" ("He draws up the drops of water, which distill as rain to the streams"). Its scarcity fuels debate. Linguistically, it may tie to Akkadian edu ("flood" or "overflow"), suggesting water rising forcefully, or to Aramaic roots hinting at "moisture." But Jewish and Christian scholars don’t stop at etymology—they see 'ed through the lens of divine intent and cosmic order.

The Context of Creation

Genesis 2:5-6 describes a world before rain or human labor, where 'ed emerges "from the earth" to water it. This sets the stage for vegetation, hinting at a natural yet God-ordained process. Does 'ed signify a gentle mist, a network of springs, or something more symbolic? Commentaries offer a spectrum of views, rooted in the text’s role as a prelude to life.

Jewish Perspectives

Jewish interpreters often emphasize practical and symbolic layers. Rashi, the medieval sage, describes 'ed as a "mist" or "vapor" rising from the earth, softening the soil for God’s later act of forming plants. He ties it to the absence of rain, suggesting a temporary hydration until humanity’s arrival. The Talmud (e.g., Ta’anit 10a) connects 'ed to the "lower waters" of creation, implying a subterranean source—perhaps springs or a flood-like surge—echoing Genesis 1’s division of waters. Nachmanides (Ramban) leans toward "mist," seeing it as a subtle, divine mechanism distinct from rain, which requires human prayer and merit. These views blend the physical (moisture from below) with the theological (God’s provision in a pre-fallen world).

Christian Interpretations

Christian commentators often frame 'ed within a broader narrative of creation and redemption. Early Church Fathers like Jerome, behind the Vulgate’s fons ("fountain"), saw it as a spring-like flow, reflecting God’s life-giving order before sin disrupted nature. Augustine, in The Literal Meaning of Genesis, entertains "mist" as a poetic image of primordial harmony, a world sustained effortlessly by divine will. Modern scholars like John Calvin stick with "mist," noting its simplicity suits a time before rain’s covenantal role (e.g., Noah’s flood). The NIV’s "streams," favored by some evangelicals, aligns with a watering system, evoking Eden’s rivers (Genesis 2:10-14).

Linguistic and Traditional Clues

The Septuagint’s pēgē ("fountain" or "spring") influenced both traditions, suggesting water rising from the earth, though "mist" gained traction in English via the KJV. Job 36:27’s "vapor" bolsters this, as does the poetic tone of Genesis. Yet the Akkadian edu ("flood") tempts some to see a stronger surge, a minority view given the text’s calm context. Jewish and Christian translators alike grapple with balancing literal meaning and spiritual depth.

Mist or Springs: A Verdict?

Synthesizing these voices, "mist" emerges as the frontrunner. Rashi and Calvin favor its gentle universality, fitting a world without rain or toil. It aligns with Job’s usage and Genesis’s ethereal vibe. "Springs" or "streams," backed by the Talmud and some Christians, offers a concrete alternative—water breaking through the earth, prefiguring Eden’s rivers. "Cloud" finds little support, drifting too far from the text’s grounding. "Flood" feels out of place in this quiet scene.

Jewish thought often sees 'ed as a bridge between creation’s waters, while Christians tie it to God’s prelapsarian care. Both agree it’s purposeful, not random. Mist edges out for its poetic fit, but springs holds ground as a tangible echo of ancient hydrology. Perhaps the ambiguity is the point—a mysterious act of divine nurture, lost to our modern eyes.

A Window to Wonder

Whether mist veiling the earth or springs bubbling beneath, 'ed invites imagination. Jewish and Christian voices don’t fully settle the debate, but they enrich it, blending word and wonder. What do you see rising from that ancient ground—vapor or stream, or something beyond both?

The most likely meaning would then seem "mist" or "vapor"—a gentle rising of moisture from the earth to water it uniformly. This fits the poetic style of Genesis, the parallel in Job, and the idea of a world not yet reliant on rain or human effort. "Springs" is plausible and practical, especially in a region familiar with underground water sources, but it feels less universal than the text implies. "Cloud" is the weakest option, as it suggests something higher in the atmosphere, disconnected from the "from the earth" detail.

Perhaps the ambiguity may be intentional, reflecting a primordial world where natural processes are still mysterious. Without a time machine or a clearer Hebrew dictionary, it seems "mist" edges out as the best fit based on context and usage, though "springs" remains a solid contender.